The Millerite Movement was a religious revival that started in 1831 when the Baptist preacher William Miller, an earnest student of the Bible, began preaching and writing about the soon return of Christ. Due to a misinterpretation of a prophecy in the book of Daniel, he and his followers concluded that Jesus Christ was coming back sometime around 1843 or 1844.

These followers, known as Millerites, were ordinary people, many already church-going Christians. Most of them were in the United States, though the movement had a worldwide impact, too.

When Jesus didn’t come back in 1844, the Millerite Movement dissolved, but it left its mark on American history. It also sparked the beginning of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, which is a thriving Christian denomination today.

Let’s explore 4 questions about this movement:

- What started the Millerite Movement?

- How did the Millerite Movement progress?

- What did the Millerites believe?

- What happened to the Millerite Movement in 1843 and 1844?

What started the Millerite Movement?

Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash

The Millerite Movement began with William Miller, a farmer-turned-preacher, and his exciting discoveries while studying prophecy in the Bible. The discovery that especially caught his attention and led him to preach about Jesus’ second coming was a prophecy in Daniel 8:14, which he believed predicted the end of the world.

But Miller hadn’t always been a Christian. In fact, in his earlier life, he had mocked Christians and their belief in the Bible.

This all changed when he served in the War of 1812. During the Battle of Plattsburg, Miller came face to face with the fragility of life when a shell exploded near him. Upon returning home, he gave his life to God and began to study the Bible from cover to cover.1

The Bible’s prophecies caught his attention.

He wondered:

If prophecies of the past had been fulfilled in a literal way, then what about the prophecies of the future?

And specifically, what about the second coming of Jesus Christ? Miller concluded that it must also be a literal event that would happen soon.2

And what he discovered would spur the Millerite Movement.

Miller’s study of Daniel 8:14

Photo by Sincerely Media on Unsplash

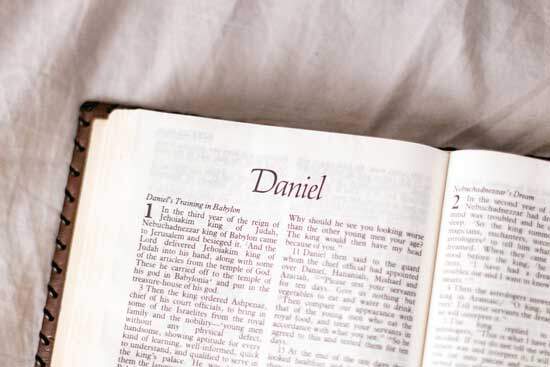

The book of Daniel, with its visions and symbols, drew William Miller in.

Especially Daniel 8:14:

“For two thousand three hundred days; then the sanctuary shall be cleansed” (NKJV).

According to the popular teachings of his time, Miller thought the sanctuary symbolized the earth. The cleansing, then, must be the fire that would cleanse the earth at Jesus Christ’s second coming.

But when would it happen?

If Miller could figure out the starting date for the prophecy, then he would know the time of Christ’s return.

Based on passages like Ezekiel 4:5–6 and Numbers 14:34, he observed that one prophetic day equals a literal year. Reformers, such as Martin Luther and John Newton, had believed in this “day-for-year” principle too.

Thus, the 2300 prophetic days represented 2300 literal years.

By studying Daniel 9:24–27, Miller found a starting date for the prophecy: 457 BC.

Here are some points from his study:

- The same angel that gave Daniel the 2300-year prophecy (Daniel 8:14) returned to explain it to him (Daniel 9:22, 23).

- The explanation included another prophecy of 490 years (Daniel 9:24–27), which had to be part of the 2300-year prophecy.

- The 490 years was supposed to begin at the time of the decree to rebuild Jerusalem.

- According to historical records, the most complete decree was issued by Artaxerxes in 457 BC (Ezra 7).

- This date, then, was the beginning of both the 490-year and 2300-year prophecies.

And if they started in 457 BC, the 2300 years would end in 1843.

That meant Jesus was coming in less than 25 years!

What was Miller to do?

The beginning of Miller’s preaching

Miller had come to his conclusions by 1818. But he wasn’t ready to share them with the world.

If he were wrong, he didn’t want to mislead anyone.

For five years, he continued to study and wrestle with the conviction to share his findings.3

In 1831, an opportunity came when Miller received an unexpected invitation to speak. It wasn’t long before more invitations were flooding in. Miller received so many that he had to reject over half of them!4

The movement was now underway, and nothing could stop it.

How did the Millerite Movement progress?

In 1840, William Miller met Joshua V. Himes, a fiery leader in the social reform movement. Himes became convinced of Miller’s message and negotiated for Miller to speak at a chapel in Boston.

It was his first speaking engagement in a large city. The turnout was so overwhelming, there wasn’t enough room for everyone!5

From then on, Himes joined forces with Miller as his promoter. He scheduled speaking opportunities and published a magazine to spread Miller’s teachings.6

At this point, the movement took off, and others began preaching the message of Jesus’ soon coming. It was particularly widespread among believers in the Christian church in New England.

The interest in Bible prophecy was growing.

Tent meetings began popping up all over. To provide the movement with some structure, Himes organized “general conferences.” These meetings allowed leaders to study the Bible and make plans for larger gatherings.

A revival, much like the Great Awakenings of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, swept throughout the country. Thousands gave their lives to God.7

A Methodist yearbook estimates that 256,000 conversions took place between 1840 and 1844!8

And the movement wasn’t limited to North America.

It was worldwide. The message of Christ’s soon coming spread throughout Germany, Holland, other parts of Europe, and even India and Asia.9

What did the Millerites believe?

The Millerites were an eclectic group from many different denominations—Baptist, Methodist, Congregationalist, Episcopalian, and Lutheran, to name a few.

But they had some things in common.

To begin, their understanding of prophecy was unique. At that time, a mainstream viewpoint in the Christian church was postmillennialism.10 This was the idea that the condition of the world would continue to improve in preparation for a thousand years of peace. When this new age began, Christ would come “spiritually” and reign in people’s hearts. But He wouldn’t come to earth in a literal sense until the end of the thousand years.

The Millerites did not agree.

They believed that the second coming of Jesus would take place before the thousand years of Revelation 20.

Furthermore, the prophecies of the Bible would take place in a literal, physical manner—just as Jesus first came to the earth.11

Jesus’ soon coming

With this framework, the Millerites looked forward to Jesus’ literal arrival.

They studied passages from both the Old and New Testament that talked about the signs and manner of that event:

- Matthew 24; Matthew 25:1–13

- Joel 2:28–30

- 1 Corinthians 15:51–53

- 1 Thessalonians 4:16–17

The first and second angels’ messages of Revelation 14

Revelation 14:6–8 was another Bible passage that shaped the views of the Millerites.

In it, angels fly from heaven with the “everlasting gospel to preach to those who dwell on the earth” (Revelation 14:6, NKJV).

The first angel calls the world to “fear God and give glory to Him, for the hour of His judgment has come” (Revelation 14:7, NKJV). The Millerites honed in on this latter part of the verse: They urged people to prepare because Jesus Christ was coming to judge the earth.

The second angel declared: “Babylon is fallen, is fallen” (Revelation 14:8, NKJV). The Millerites understood “Babylon” as a reference to the confusion of false teaching. It applied to churches that had refused to accept God’s truth.

As the Christian church at large rejected Jesus’ soon coming,12 the Millerites chose to leave their denominations in obedience to this second angel’s message.

What happened to the Millerite Movement in 1843 and 1844?

Photo by Aron Visuals on Unsplash

The Millerites eagerly awaited Jesus’ return, first in 1843 and then in 1844. In the process, they would undergo many disappointments, culminating in the Great Disappointment on October 22, 1844.

Let’s look at how it happened.

The “tarrying” time

Miller preached that Jesus Christ would come sometime between March 21, 1843, and March 21, 1844.13 But 1843 came and went. Then the spring of 1844 passed. The discouraged Millerites called this period the “tarrying time,” which meant a time of waiting or delay.

The phrase came from Habakkuk 2, in which the prophet Habakkuk cried to God for justice. He received the assurance that the coming of God and His kingdom would be the answer to that cry.

But it would be delayed.

The Millerites applied Habakkuk 2:3 to the delay in Jesus’ coming that they were experiencing:

“The vision is yet for an appointed time;

But at the end it will speak, and it will not lie.

Though it tarries, wait for it;

Because it will surely come,

It will not tarry” (NKJV).

And what happened next sparked the movement back to life.

The Midnight Cry

Photo by Artiom Vallat on Unsplash

At a New England tent revival meeting in August 1844, a Millerite named Samuel Snow came riding in with a message. His message would become known as “the Midnight Cry,” based on the Parable of the Ten Virgins (Matthew 25) in which a cry at midnight announced the return of the bridegroom—a parallel to the return of Christ.

When Samuel Snow was given the floor to speak at the meeting in New England, he explained that the calculation of the 2300-year prophecy had been off. Jesus would not come until October 22, 1844.

Here’s why:

First, he realized that the decree to rebuild Jerusalem in 457 BC didn’t reach Jerusalem until the fifth month of the year (Ezra 7:8). Since the Jewish year began in the spring, that would have positioned the 2300-year prophecy to end sometime in the fall.

Second, the cleansing of the sanctuary mentioned in Daniel 8:14 was closely connected to the Jewish feast called the Day of Atonement. This event always fell on the tenth day of the seventh month of the Karaite Jewish calendar. In 1844, it was supposed to occur on October 22nd.14

That was only a couple of months away!

Snow’s message aroused the Millerites like never before.

One Millerite wrote:

“It swept over the land with the velocity of a tornado, and it reached hearts in different and distant places almost simultaneously.”15

As people proclaimed the soon coming of Jesus, they lived out their faith too. Storeowners closed their shops to spread the message. Farmers chose not to harvest their crops.16

But the Millerites were to be disappointed again.

October 22, 1844 came and went.

Jesus didn’t come.

After this date, the Millerite Movement petered out. Many disillusioned Millerites walked away for good. Others tried to reconcile why Jesus Christ hadn’t returned.

But amid their disappointment, some in this latter group went back to the Bible and eventually formed new denominations, including the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

The influence of the Millerite Movement lives on

Because the Millerites misunderstood October 22, 1844, they faced bitter disappointment.

But even through the disappointment, God was still working.

The Millerite movement planted important seeds about biblical prophecy and the Second Coming that would inspire diligent Bible study. And at that point in history, it was more common for church-goers to leave the Scripture-searching to the clergy. So this growing amount of personal conviction to study the Bible was significant.

The results of this deep dive into Scripture led to the Advent Movement.

This cohesive community of believers kept studying together and eventually organized in 1863 to become the Seventh-day Adventist Church. And a handful of prominent former Millerites, like Joseph Bates and James and Ellen White, became its pioneering leaders.

And this hope of the Second Coming still inspires Adventists today.

To learn more about the growth of the Seventh-day Adventist Church and its beliefs, start with our article “Who are Seventh-day Adventists?”

- Bliss, Sylvester, and Hale, Apollos, Memoirs of William Miller, (J.V. Himes, 1853), p. 68–69. [↵]

- Ibid., p. 72. [↵]

- Ibid., p. 81, 92. [↵]

- Ibid., p. 99. [↵]

- Maxwell, C. Mervyn, Tell It to the World, (Pacific Press, Nampa, ID, 1977), p. 16. [↵]

- Bliss and Hale, p. 104. [↵]

- Maxwell, p. 18–20. [↵]

- Bliss and Hale, p. 117. [↵]

- Loughborough, J. N., The Great Second Advent Movement, (Adventist Pioneer Library, Jasper, Oregon, 2016), p. 85–91. [↵]

- Pointer, Steven R., “American Postmillennialism: Seeing the Glory,” Christianity Today, No. 61, 1999. [↵]

- Bliss, Hale, and Himes, “Vindication,” Advent Herald, Nov. 13, 1844. [↵]

- Maxwell, p. 27. [↵]

- Maxwell, p. 26. [↵]

- Maxwell, p. 30–31. [↵]

- Southard, N., Midnight Cry, Oct. 31, 1844. [↵]

- Bliss and Hale, p. 141. [↵]

More Answers

What Does “Adventist” Mean

Seventh-day Adventists are a Protestant Christian denomination who hold to the biblical seventh-day Sabbath. From this belief, they get the first part of their name.

William Miller

William Miller was a farmer in the early 1800s who gave his life to God and began intensely studying his Bible.

Joseph Bates

Joseph Bates was a sailor-turned-preacher who joined the Millerite Movement and waited for Jesus to come in 1844. Despite being disappointed when this didn’t occur, Bates held onto his faith and played an enthusiastic and integral part in starting the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

Who was J.N. Andrews and How Did He Contribute to Adventism?

John Nevins Andrews (1829–1883) was an influential leader in the early days of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. He was a Bible scholar who helped shape several Adventist beliefs and juggled many roles in the Church. Most notably, he was the first official missionary for the Adventist Church outside North America.

Seventh-day Adventist Founders

The key figures and founders of Seventh-day Adventism were a group of people from various Protestant Christian denominations who were committed to studying the Word of God and sharing about Jesus Christ.

What is the Great Disappointment and What Can We Learn From It?

On October 22, 1844, thousands of Christians in the Northeastern United States eagerly watched the skies for what they believed would be the second coming of Jesus Christ.

Who Was James Springer White?

James Springer White (1821–1881) was a key figure in the Seventh-day Adventist Church and the husband of Ellen G. White.

Didn’t find your answer? Ask us!

We understand your concern of having questions but not knowing who to ask—we’ve felt it ourselves. When you’re ready to learn more about Adventists, send us a question! We know a thing or two about Adventists.